Cloud-Native Apps Don’t Require a Cloud

The irony is delicious with the buzzword of the day: cloud-native.

The first thing to note is that cloud-native, despite its name, does not require cloud. I know, right? The name comes from the architectural approach of building an application that relies on infrastructure and is designed around the concepts of cloud: elasticity, economy of scale, and distributed computing. It is inarguably cloud computing that has driven these concepts into every aspect of application delivery: from app architecture to automation, from API-based integration to infrastructure. Cloud computing has changed the way in which we go about developing, building, and deploying applications. Apps that were born in the public cloud naturally assumed many of the same dependencies and characteristics. Thus, the name accurately represents the etymology of the architectural style.

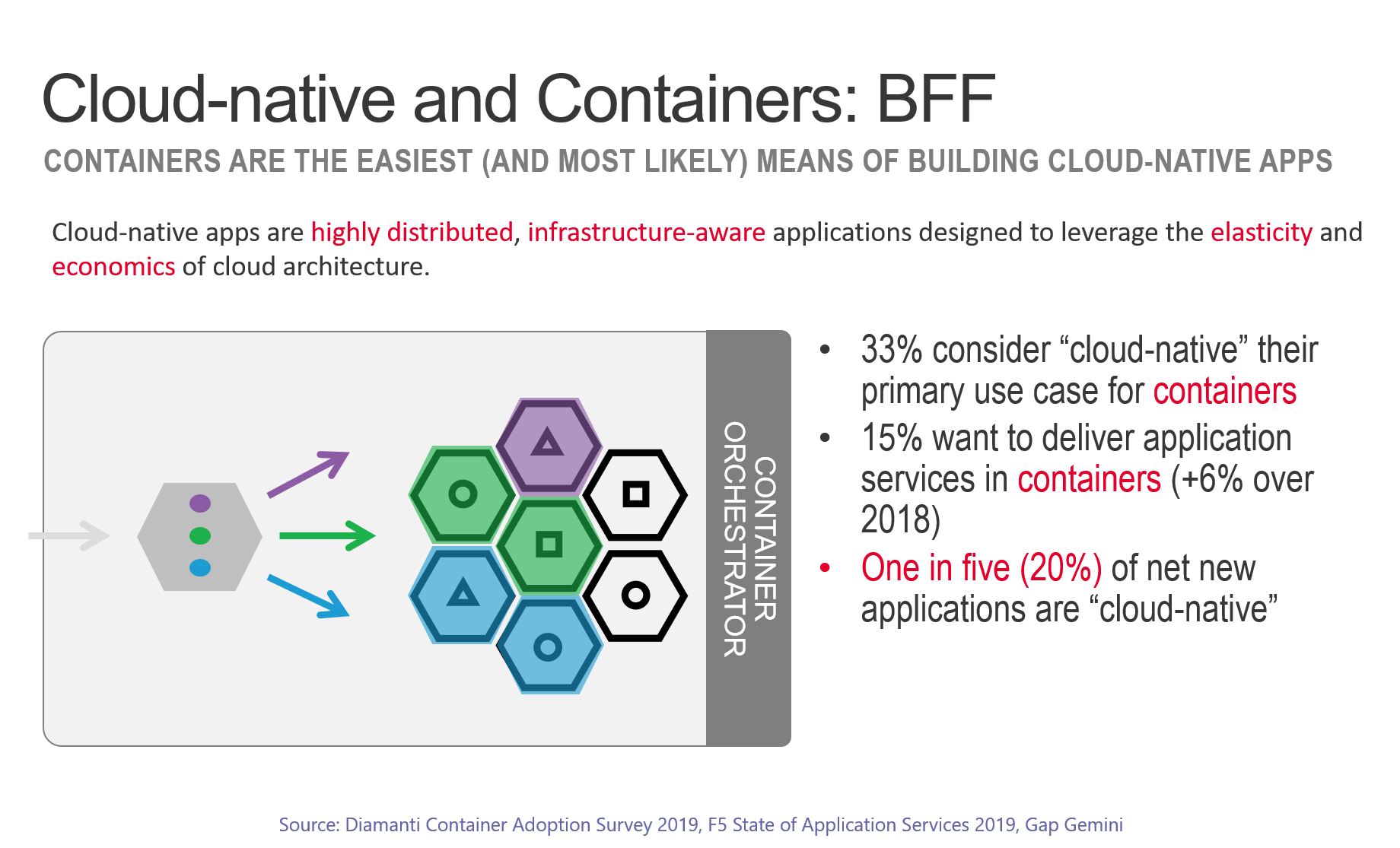

There is also inarguably a link between cloud-native and containers. That in itself makes it different from born-in-the-cloud apps that primarily rely on virtual machines and cloud-native services to achieve similar goals. Cloud-native and containers are tightly coupled because the associated container orchestrators (Kubernetes) are the easiest and most prevalent means of coupling applications with the infrastructure required to deliver elasticity and, through it, the economy of scale desired.

In a cloud-native application, components are atomized to support economy of scale. Hence the reason cloud-native and containers are nearly synonymous. You need to be able to scale only the functions that are in demand, on-demand. This kind of elastic, functional partitioning of applications has traditionally been achieved through architectures that rely on layer 7 (HTTP) routing and cloud-native is no exception. The same principles apply to these modern applications and generally make use of an ingress controller (an infrastructure application service) that manages distribution of inbound requests to the appropriate container-based instance of an application component.

This partitioning is often conducted at the API level, where URIs are matched to API calls that are matched to specific container Services. The ingress control directs requests to the appropriate container Service and it, in turn, distributes requests across a pool of component/application instances. This is a two-layer cake with layer 7 (HTTP) ingress control distributing to a plain old load balancer (POLB) for delivery and fulfillment.

Additionally, we've got the reliance on service registries which, under the covers, is another infrastructure application service required to facilitate elasticity of cloud-native applications. Without a service discovery mechanism, load balancing and ingress control fail to operate, which in turn makes the application inoperable.

This relationship - between components, services, service registries, load balancers, and ingress control - is the incarnation of the principles of cloud-native applications. Application components and infrastructure are intimately linked without being tightly coupled. Components cannot achieve the economy of scale or distribution across environments without the layer 7 routing and plain old load balancing capabilities. The dependency between infrastructure and applications is real and critical to the business imperative to deliver apps.

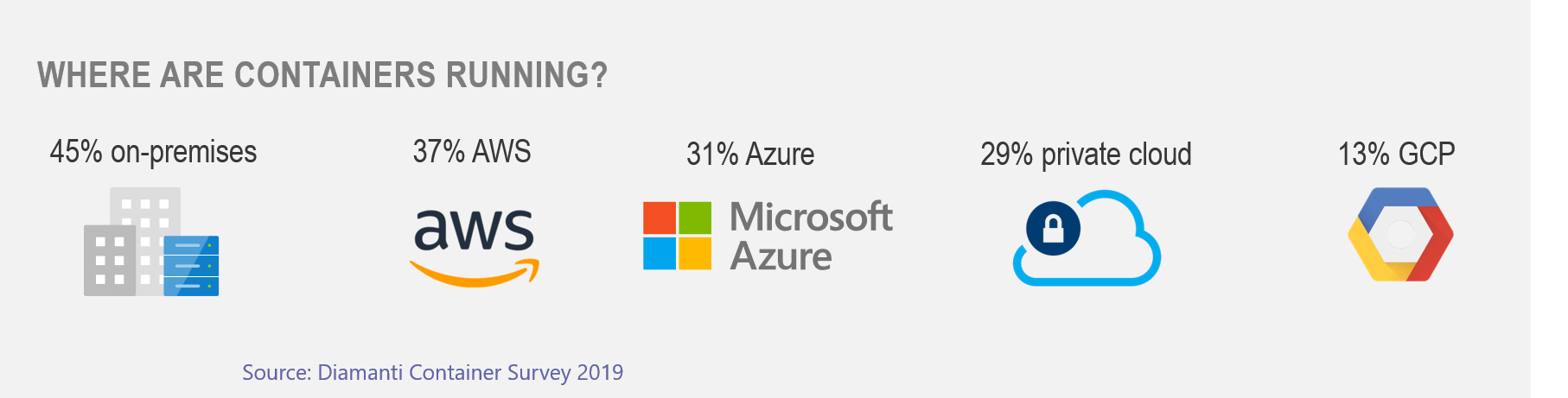

None of this relies on or requires any kind of cloud computing environment. A cloud-native application can be - and is often - deployed on its own. In fact, if we look to data regarding containers and where they're running, we find that "on-premises" maintains its ascendancy over public cloud environments.

Now, while it's certainly true that one could be deploying containers on a private (on-premises) cloud - and indeed our own research continues to show that on-premises private cloud remains the most popular cloud model in use. More than three-quarters (79%) of respondents in our State of Application Services 2019 have applications in an on-premises, private cloud while public cloud continues to struggle to reach a majority at 45%.

Cloud-native applications are a fast-growing architecture that you can be sure will continue to grow over the next five years. Understanding their relationship to - and dependency on - infrastructure application services is a critical component to successfully delivering (and securing) these modern applications.